"What are you writing?" the Rebbe asked. "Stories," I said. He wanted to know what kind of stories: true stories. "About people you knew?" Yes, about things that happened or could have happened. "But they did not?" No, not all of them did. In fact, some were invented from almost the beginning to almost the end. The Rebbe leaned forward as if to measure me up and said with more sorrow than anger: "That means you are writing lies!" I did not answer immediately. The scolded child within me had nothing to say in his defence. Yet, I had to justify myself: "Things are not that simple, Rebbe. Some events do take place but are not true; others are - although they never occurred."

("Legends of Our Time" by Elie Wiesel, New York Holt,

Rinehart and Winston, 1968, p. viii)

Excerts from source below are largely a review of "The Holocaust in American Life" by Peter Novick:

THE UNIQUENESS OF THE HOLOCAUST

[...]

The most commonly expressed grievance was the use of the words "Holocaust" and "genocide" to describe other catastrophes. This sense of grievance was rooted in the conviction, axiomatic in at least "official" Jewish discourse, that the Holocaust was unique. Since Jews recognized the Holocaust's uniqueness-that it was "incomparable," beyond any analogy-they had no occasion to compete with others; there could be no contest over the incontestable. (Novick 1999, 195)

As Novick notes (1999, 196), one can always find ways in which any historical event is unique. However, in Lipstadt's eyes, any comparison of the Holocaust with other genocidal actions is not only factually wrong but also morally impermissible and therefore the appropriate target of censorship. Lipstadt clearly places herself among those who would not merely criticise but censor scholarship that places the Holocaust in a comparative framework-i.e., scholarship that questions the uniqueness of the Holocaust (Novick, 1999, 259). Novick (1999, 330n.107) quotes Lipstadt as follows: Denial of the uniqueness of the Holocaust is "far more insidious than outright denial. It nurtures and is nurtured by Holocaust-denial." In Denying the Holocaust, Lipstadt castigates Ernst Nolte and other historians who have "compared the Holocaust to a variety of other twentieth-century outrages, including the Armenian massacres that began in 1915, Stalin's gulags, U.S. policies in Vietnam, the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, and the Pol Pot atrocities in the former Kampuchea" (Lipstadt, 1993, p. 211). Lipstadt calls these "attempts to create such immoral equivalencies." In the section on the uniqueness of the Holocaust, she cites approvingly the claim that "the Nazis' annihilation of the Jews . . . was 'a gratuitous [i.e., without cause or justification] act carried out by a prosperous, advanced industrial nation at the height of its power'" (p. 212).

[...]

From my perspective as an evolutionist, bloody and violent ethnic conflict has been a recurrent theme throughout history. The attempt to say it is unique is an attempt to remove the Holocaust from the sphere of scholarly research, interpretation and debate and move into the realm of religious dogma, much as the resurrection of Jesus is an article of faith for much or Christianity. By accepting the type of censorship promoted by Lipstadt's writings we are literally entering a new period of the Inquisition wherein religious dogma rather than open scientific debate is the criterion of truth.

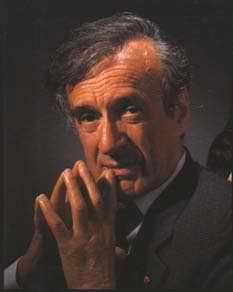

Peter Novick has a great deal of interesting material on the political campaign for the uniqueness of the Holocaust. In the same discussion where he comments on Lipstadt's statements on the uniqueness of the Holocaust, he notes Elie Wiesel's idea of Holocaust "as a sacred mystery, whose secrets were confined to a priesthood of survivors. In a diffuse way, however, the assertion that the Holocaust was a holy event that resisted profane representation, that it was uniquely inaccessible to explanation or understanding, that survivors had privileged interpretive authority-all these themes continued to resonate." (i.e., in recent years) (Novick, 1999, 211-212).

Novick also describes a massive campaign to make the Holocaust a specifically Jewish event and to downplay the victim status of other groups. Speaking of 11 million victims was clearly unacceptable to [Elie] Wiesel and others for whom the "big truth" about the Holocaust was its Jewish specificity. They responded to the expansion of the victims of the Holocaust to eleven million the way devout Christians would respond to the expansion of the victims of the Crucifixion to three-the Son of God and two thieves. Wiesel's forces mobilised, both inside and outside the Holocaust Council, to ensure that, despite the executive order, their definition would prevail. Though Jewish survivors of the Holocaust had no role in the initiative that created the museum, they came, under the leadership of Wiesel, to dominate the council-morally, if not numerically. When one survivor, Sigmund Strochlitz, was sworn in as a council member, he announced that it was "unreasonable and inappropriate to ask survivors to share the term Holocaust . . . to equate our suffering . . . with others." At one council meeting, another survivor, Kalman Sultanik, was asked whether Daniel Trocme, murdered at Maidanek for rescuing Jews and honoured at Yad Vashem as a Righteous Gentile, could be remembered in the museum's Hall of Remembrance. "No," said Sultanik, because "he didn't die as a Jew. . . . The six million Jews . . . died differently." (Novick 1999, 219)

Activists insisted on the "incomprehensibility and inexplicability of the Holocaust" (Novick 1999, 178). "Even many observant Jews are often willing to discuss the founding myths of Judaism naturalistically-subject them to rational, scholarly analysis. But they're unwilling to adopt this mode of thought when it comes to the 'inexplicable mystery' of the Holocaust, where rational analysis is seen as inappropriate or sacrilegious" (p. 200). Elie Wiesel "sees the Holocaust as 'equal to the revelation at Sinai' in its religious significance; attempts to 'desanctify' or 'demystify' the Holocaust are, he says, a subtle form of anti-Semitism" (Novick 1999, 201). A 1998 survey found that "remembrance of the Holocaust" was listed as "extremely important" or "very important" to Jewish identity-far more often than anything else, such as synagogue attendance, travel to Israel, etc.

Reflecting this insistence on the uniqueness of the Holocaust, Jewish organisations and Israeli diplomats co-operated to block the U.S. Congress from commemorating Armenian genocide. "Since Jews recognized the Holocaust's uniqueness-that it was 'incomparable,' beyond any analogy-they had no occasion to compete with others; there could be no contest over the incontestable" (p. 195). Abraham Foxman, head of the ADL, stated the Holocaust is "not simply one example of genocide but a near successful attempt on the life of God's chosen children and, thus, on God himself" (p. 199).

Novick has also shown how the Holocaust successfully serves Jewish political interests. The Holocaust was originally promoted to rally support for Israel following the 1967 and 1973 Arab-Israeli wars; "Jewish organisations . . . [portrayed] Israel's difficulties as stemming from the world's having forgotten the Holocaust. The Holocaust framework allowed one to put aside as irrelevant any legitimate ground for criticizing Israel, to avoid even considering the possibility that the rights and wrongs were complex" (p. 155). As the threat to Israel subsided, the Holocaust was promoted as the main source of Jewish identity and in the effort to combat assimilation and intermarriage among Jews. During this period, the Holocaust was also promoted among gentiles as an antidote to anti-Semitism. In recent years this has involved a large scale educational effort (including mandated courses in the public schools of several states) spearheaded by Jewish organisations and manned by thousands of Holocaust professionals aimed at conveying the lesson that "tolerance and diversity [are] good; hate [is] bad, the overall rubric [is] 'man's inhumanity to man'" (pp. 258-259). The Holocaust has thus become an instrument of Jewish ethnic interests as a symbol intended to create moral revulsion at violence directed at minority ethnic groups-prototypically the Jews.

See Also:

- He-lie Wiesel: Yes, we really did put God on trial at Auschwitz - Verdict: "He owes us something"

- Elie Wiesel: Prominent Liar and Anti-German Hatemonger; Claims Jews "burned alive in flaming ditches" and "ground spurted geysers of Jewish blood"

- Quotes from Elie Wiesel on the Holocaust™

- Where is Elie Weasel's Auschwitz Tattoo?

- Elie Wiesel on the "baby burning pits" at Birkenau

- Elie Wiesel's Geysers of Blood at Babi Yar, Ukraine