The story is that Samuel survived the "death" camps of Majdanek, Auschwitz and Dachau.

That's funny, because now even Holohoax propagandists acknowledge that both Majdanek and Dachau were not extermination camps. Oh well, let's not spoil Samuel's and the Jew York Times' fun.

The Germans tried twice to kill Samuel by putting him in the gas chamber, but Samuel escaped by telling the guard that he was only there to wash the floor.

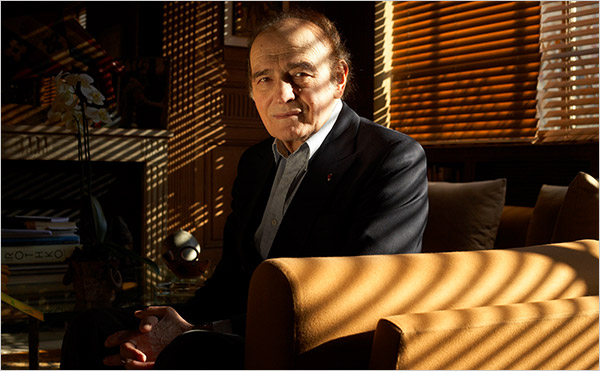

The Saturday Profile

After Survival, a Journey to Self-Recovery

Samuel Pisar, a Jewish survivor of Majdanek, Auschwitz and Dachau,

the Nazi concentration camps.

Published: July 10, 2009THE concert was a memorial to the victims of the Warsaw ghetto, and it was also, to Leah Pisar, a sort of homecoming. “It was so much more resonant there than elsewhere,” she said. “Yad Vashem is the place where one feels closest to those who perished. It was as if he was saying Kaddish for all the six million.”

He likes to talk of the cunning child inside him. In May, in Bialystok, Poland, where he was born, he said, “I am not sure which of my two voices is more authentic, or more relevant for survival in our crisis-ridden world.”

He is not sure, but he suspects. His Kaddish is also an argument with other men about the degradation of the world in the name of big ideas. But it is also a memorial to his lost family, when he recites, “My memory is the only tomb they have.”

The family’s tradition of public service continues. Leah Pisar worked in the State Department and White House under President Bill Clinton. His stepson, Antony J. Blinken, is national security adviser to Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr. Mr. Pisar also has two daughters from his first marriage.

The German government still pays him, as a survivor, $700 a month, “but I’ve never been able to invest it in a normal way,” he said. For all the money he has made and given away, “that money is still intact.”

He wrote that he would use it to create some physical memorial to his parents, “and I will get around to it,” he said uncomfortably. “My children say to me, I have to do it,” he said, “and one day I will, sooner rather than later.”

He talks of being open now, but he keeps much hidden. He says he is better with his grandchildren than his children. Even with Leah, he said, “I was willing to tell her a little but not a lot — I fenced with her a little.”

Later, he said, “I never spoke about the real horrors — not even with the Germans.” Then later: “I remember every detail. But I don’t suffer from it.” And then he said: “It helped me in life. And tragic as it was, it was a positive experience. I would never have been the way I am.”

The Kaddish has liberated him, he said; he feels more at ease with the mystery of God. “It’s not just that he’s waiting for me,” Mr. Pisar said. “I’m more at peace. I’m ready.”

A version of this article appeared in print on July 11, 2009, on page A8 of the New York edition.

Source: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/11/world/europe/11profile.html?_r=1

Article: "After Survival, a Journey to Self-Recovery"