[From the Vienna Fremden Blatt, of November 14, 1889.)

At Wadomice, a town of Galicia, but little known, a trial is now taking place, the interest of which extends far over the limits of this monarchy. The crime imputed to the accused, "trade of emigrants to America," was committed by the same persons at the same time in Austria-Hungary and Germany. The prosecuting attorney, Tarnowsky, referring to this "trade," says in one part of his accusation that "there existed within the limits of Austria a territory which actually was beyond the reach of the law, where, in defiance of order and personal liberty, all kinds of tricks were played upon unfortunate emigrants." Nor did the prosecuting attorney omit to name the high officials who not only suffered this state of things to go on, but who, in some instances, even prompted the perpetration of these crimes.

As far as the police is concerned, it must be owned with shame that it lent a willing hand for a monthly remuneration or a certain percentage, and that, instead of preventing crimes, they committed them. In mitigation, however, it must be said that they were subject to the orders of the district authorities, whose instructions, as they allege, they simply carried out.

This trial also proves again the well-known fact that criminals are a fraternity, which is international and interconfessional. Polish, German, and Hungarian criminals here go hand in hand to cheat and rob Polish, German, and Hungarian emigrants. Christians and Jews for years carried on a nefarious traffic in human beings, selected alike from the ranks of Christians and Jews. Criminals flock together everywhere: they understand each other without regard to nationality and religion.

All the accused (sixty-five in number) were divided into 28 sections, and arraigned on the following charges: Violence and privation of personal liberty (par. 93), extortion (par. 98), abuse of official power (pars. 101 and 1021, accepting bribes (par. 104), bribing others (seduction) to abuse official power (par 105). robbery (par. 109), fraud (par. 197), false assumption of N official title (par. 199), concealment of deserters (par. 290), and inducing soldiers to desert (par. 222). The names of the principal offenders are: Julius Neumann, keeper of railway refreshment room at

Auschwitz; Jacob Klausner, merchant; Simon Herz, cattle-dealer; Julius Lowenberg, merchant; Marcell Iwanicki, internal-revenue officer and chief of police; Adam Kastocki, custom-house official; Arthur Landau, merchant; Isaac Lunderer, merchant; Josef Eintracht, manufacturer of varnish; Herman Zeitlinger, railway door-keeper; Ernest Edward Zopoth, cashier at the railway station at

Auschwitz, and Vienna Zwilling, farmer.

STATISTICS CONCERNING EMIGRATION.

Inquiries made by the courts of justice show that emigration to America from some of the districts of Galicia has assumed gigantic dimensions. In proportion to emigration is the sale of farms and the spread of pauperism, and if the books of the agent of the Hamburg steam-ship line seized at

Auschwitz

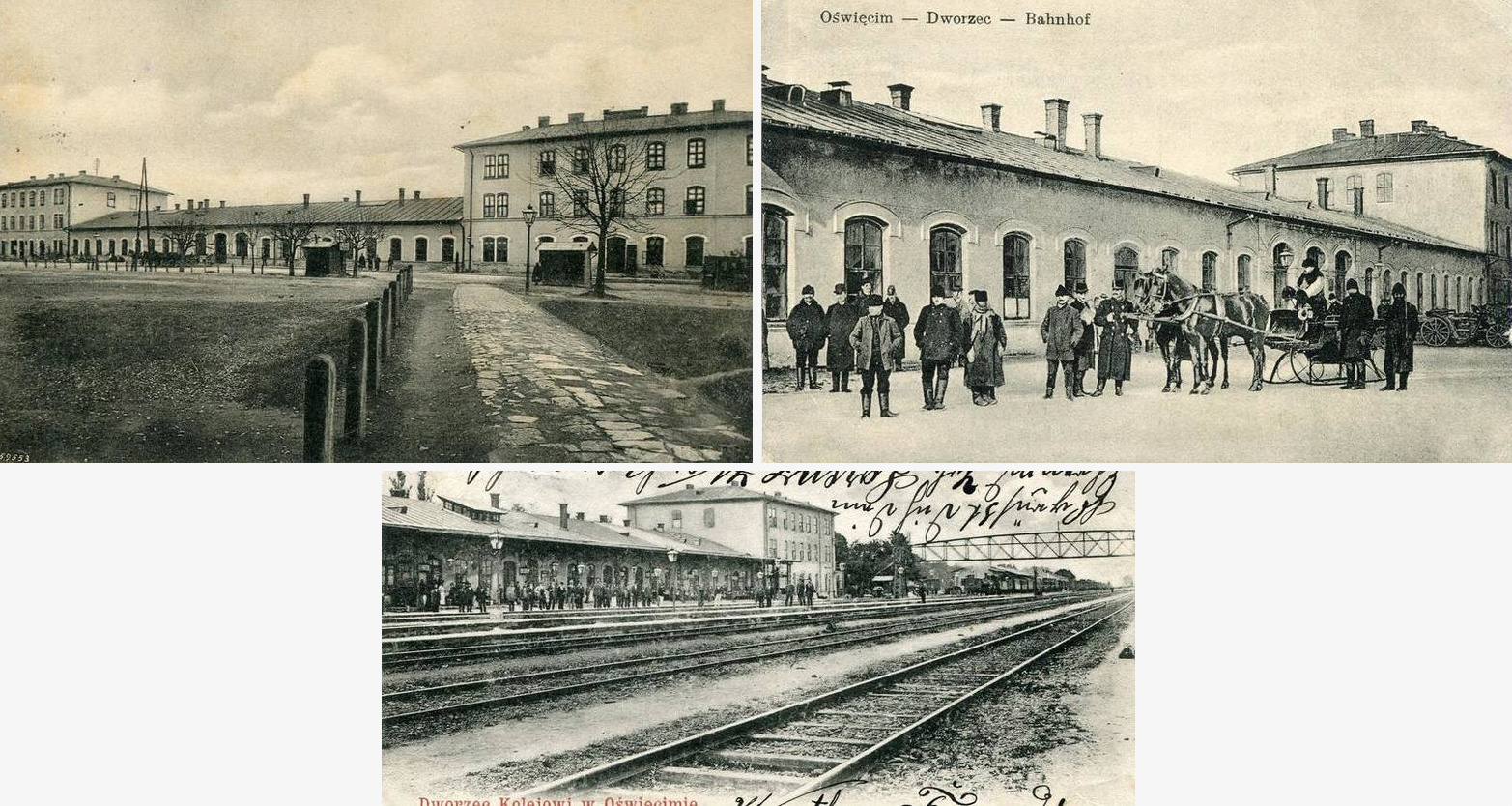

show that from May. 1887, to July, 1888, the sum of 695,051 florins was received for passage tickets, after deduction of agent's provision, and that the agent of the North German Lloyd took in the course of two months 27,313 florins, the sums are by no means all enumerated which annually find their way abroad. The reason why Auschwitz was selected by the steam-ship lines as the main point where to establish their agencies in Galicia was because it is the only town which is in direct railway communication with the German sea-ports.

The most notorious of the agents appointed by the Hamburg Lino was the. leaseholder of the railway refreshment rooms at

Auschwitz—Julius Neumann. His outrageous conduct at last attracted the attention of the railway company, who gave him the choice to either give up the agency or the lease of the restaurant. As the. former could flourish only as long as he was at the same time lease-holder of the restaurant, he made over the latter, "pro forma," in 1882 to Herz & Lowenberg, but remained as silent partner. In this way the first emigration company was started at

Auschwitz. Their immense gains soon created competition, which reached its climax when the controller of the custom-house and the commissary of police formed a partnership with the railway cashier and the door-keeper, and established an agency for emigrants on the premises of the railway depot. No emigrant could escape them, because every passenger had to come in contact with one or the other of these officials. The last established agency authorized by the provincial government was that of Klausener, at Brodly, who was the agent of the Cunard Steam-ship Company.

For some time the competing companies, by reducing the fares and increasing the commission of their agents, tried to monopolize the trade each for itself, until in 1886 they formed a ring, regulated the prices, and consolidated the different companies under one firm, authorized by Government, and styled the

"Hamburg Agency at Auschwitz."

Competition having now come to an end, they could henceforth more effectually fleece the emigrants by charging arbitrary prices.

DIVISION OF LABOR.

After consolidation had taken place, a system was organized to hire subagents, runners, and a force of men armed and provided with clubs, who had to escort the emigrants from the railway station to the hotel, owned by one of the company, where exorbitant prices were charged them for the poorest kind of accommodation, until the time had come for their departure.

OFFICIAL CORRUPTION.

We now come to the worst feature of the case. Railway officials, as well as police and revenue officers, were induced by the agents to give their aid, for a monthly pay, and they not only suffered this state of things to go on, but even took an active part in it. One Bezirkshauptmann (chief officer of the county) named Foderick, received an annual salary of 1,000 florins. Not only the Austrian officials allowed themselves to be bribed, but also the Prussian frontier guards accepted money from the agents. Nothing, in fact, was left undone to turn the stream of emigration to

Auschwitz. Whenever emigrants refused to buy their tickets there or had already a ticket which had been sent to them from America, then the commissary of police appeared on the scene. This unscrupulous and avaricious official came to the railway station on the arrival of every train arrayed in full uniform, and had those emigrants pointed out to him by his agents, who accompanied the train, who had bought their tickets already or were going by other lines. They were then ordered to enter the office of the police commissary to show their documents and their money; and the tickets which they already had were confiscated, the commissary ordering them in his character of imperial royal police officer to purchase tickets at the imperial royal agency otherwise he would be compelled to arrest them and send them home again. Those who had no money to buy a second ticket were handed over to the police constables to be sent home.

DANGEROUS COMPETITION.

After the opening of the Bremen agency, in May, 1888, the situation of the company became more difficult. A new philanthropist made his appearance on the stage, the owner of real estate and member of numerous corporations, Vincenz Zwilling. He was intrusted with the management of this agency in the fall of 1887 by the agent of the North German Lloyd at Krakow. At first he did not seem to be in a hurry to establish himself; he was probably negotiating with the rival company to come to terms with him. When he found that his efforts in that direction were fruitless he mounted the high horse of patriotism and philanthropy and petitioned the provincial government, claiming to have been solicited by the gentry to take charge of the Bremen agency because he could no longer stand quietly and see the wicked doings of the Hamburg agency. To prevent the public, however, from mistaking the Bremen agency for the Hamburg agency, he demanded the closing of the latter. This request the authorities did not grant, but he was allowed to open his agency in May, 1888.

The commission which the company allowed him was 3½ florins for each passenger, guarantying him, aside from his annual income of 6,000 florins, with no other duty to perform except to sign his name to the passage ticket. Zwilling thereupon commenced to organize his clerical staff. He engaged none but persons who had gained their experience at the Hamburg agency, and who knew all their secrets. The energy displayed is proven by the fact that from May 10 to July 24 Zwilling received for commission 1,781 florins, and Zeitinger, his chief clerk, 400 florins. The struggle between the two competing agencies was a most desperate one, and fights were of frequent occurrence at remote villages, at railway stations, and in the cars between the representatives of rival agencies.

The scenes at the railway depot at Auschwitz, where the armed runners of both agencies posted themselves to receive the emigrants, defy description. Blood flowed freely, each party trying to get possession of the emigrants, who thereby suffered as much as the runners themselves by being knocked about. After the fight was over each party drove its victims to its own agency.

The office of the Hamburg agency was divided off in the center by a railing, in front of which stood crowded together the emigrants, while behind it strutted a person attired in a fancy uniform, trying to make believe that he was an imperial official, while his clerks addressed him as "Herr Bezirkshauptmann." A picture of the Emperor, in life-size, adorned the wall, for the purpose of giving the room the air of an imperial office. Outside the door were posted several runners, with orders to let nobody in or out during proceedings. The emigrants were then told to hand over their documents and their cash, which they usually did without any remonstrance. Arbitrary prices were demanded for tickets. In case of refusal the commissary of police was sent for, who appeared in full uniform, and threatened with arrest and transportation home. If threats had no effect, he would slap their faces and threaten to hand them over to the military authorities for evading military duty. This would invariably have the desired result. If an emigrant was short of money, the agent would telegraph in the emigrant's name to the relatives to send some.

Nor did the robbery end here. One of the clerks, Halatek, conceived the idea of bringing an alarm-clock to the office, when immigrants were told that a telegram had to be sent to Hamburg to find out whether there was still a vacant berth. The alarm-clock was set in motion, and after a while an answer came back, for which the emigrant, as a matter of course, had to pay. Telegrams were also sent to the "American Emperor" to find out whether he would permit the landing of a certain emigrant. All these "telegrams" had to be paid for by the emigrant. Another trick to extort money was for one of the clerks to put on a fancy uniform and pretend to be a surgeon to examine the emigrants and find out whether they were fit to go to America. This "examination" also had to be paid for. Sometimes an emigrant was pronounced to be unfit and he was given to understand that by offering 10 florins the "surgeon" he would be passed, which was frequently done. Passports for America were also issued and charged for with 10 or 20 florins. At the Hotel de Zator, kept by one of the gang, the emigrants had to pay exorbitant prices for the poorest kind of accommodations. What was left to them in Austria was finally taken away from them when they reached Hamburg.

From May, 1887, to July, 1888, 5,799 persons, aged from twenty to thirty-two years and liable therefore to military duty, were taken from the population.

Finally, however, the catastrophe came. A week before the closing of both agencies the agents were threatened with criminal proceedings and the publication of each other's doings. At the beginning of July, 1888, the governor of the province of Galicia and the president of the police at Krakow, instructed a police officer to proceed to

Auschwitz

and make a full report. On his arrival there a last attempt was made to avert the impending ruin by Landerer, who tried to bribe the officer by offering him 50 florins and a valuable ring. The officer accepted both, and, after depositing them, reported everything to his superiors who, after investigation, arrested the whole gang. Three hundred and seventy-seven witnesses will give testimony at the main trial, during which no less than four hundred and thirty-nine letters and other communications will be read, among the latter two communications from the ministry of public defense; depositions of the Austro-Hungarian consulates in Bremen, Hamburg, and New York; statements made by the minister of war, and a letter of the ministry of the interior of the German Empire.

Quoted in: Report of the Select Committee on Immigration and Naturalization : and testimony taken

by the Committee on Immigration of the Senate and the Select Committee on Immigration and

Naturalization of the House of Representatives under concurrent resolution of March 12, 1890,

51st Congress, 2nd Session, Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1891, pp. 946 - 949.