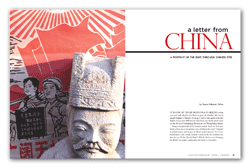

A Letter from China

A Portrait of the Jews Through Chinese

Eyes

By Susan Fishman Orlins

It is one of those mornings in

Beijing when you can’t tell whether it’s likely to

pour or whether the sun is simply behind a blanket of smog.

I stuff a rain jacket into the basket of my new $40 bicycle

and, from my hotel, pedal west to the 10-level Wangfujing

Bookstore on Wangfujing Street.

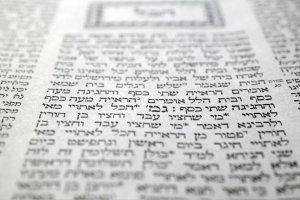

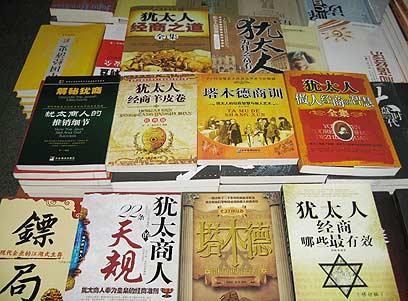

Along a cramped aisle of the business

section, heads are bent over books whose cover art includes

stars of David, the word “Talmud” in gilded letters and

moment/images of Moses embracing the Ten Commandments. I ask

a small, fortyish woman if she can translate one title for

me. It’s the “Jewish People’s Bible for Business and

Managing the World,” she replies, adding that the book

is a bestseller.

I pick up a book whose cover reads, in

Chinese and English, The Wisdom of Judaic Trader,

and flip through the pages, which are illustrated with

big-nosed caricatures. Other tomes that people around me are

reading offer morals via spiritual fables; some barely

mention religion. In many, the content is simply fabricated,

highlighting, for instance, the success of financier J.P.

Morgan (who was Episcopalian, not Jewish). I walk upstairs

to peruse the broad selection of child-rearing books and

notice a Chinese man, a little boy by his side, engrossed in

The Jewish Way of Raising Children. I ask why this

title interests him. “Because the Jewish people are very

clever,” he answers.

In this land of 1.4 billion, the

widespread perception of Jews as masters of commerce (and

much more) has given rise to an entire genre of Jewish

how-to literature. While few Chinese can articulate quite

what a Jew is, many believe that if they could emulate,

among other things, how Jewish parents raise their

children—as though there were a prescription—it would boost

their offspring’s chances of growing up to own a bank or win

Nobel Prizes. Here’s how one thread goes: Einstein was

Jewish, Einstein was smart; therefore, Jews are smart.

These powerful impressions of Jewish

accomplishments are common in the most developed regions of

China, all of which are in the midst of an economic

explosion; more skyscrapers will have been built across

China this year than exist in all of Manhattan. But amid the

bamboo scaffolding and the accompanying materialism and

corruption, people have also begun to search for moral

guidance—which some associate with the Jewish mystique—as

they sprint down the path to prosperity.

Outside the bookstore I

stroll through the old neighborhood where I lived for a year

in 1980. Past the vendors hawking roasted corncobs on sticks

and steaming sweet potatoes is the hospital where I picked

up my adopted daughter more than 20 years ago. Back then my

Chinese friends never mentioned Jews; school texts made

scant, if any, reference to Jewish history.

Then, as now, the only Chinese who called

themselves Jewish—numbering in the hundreds—were the

descendants of Persians who traveled the Silk Road a

millennium ago. They had arrived with camels, bearing

cottons to trade for silks, and many never left. Several

thousand settled in Kaifeng, the capital of the Song Dynasty

that hummed with teahouses and restaurants. Today the

Kaifeng Jews know little about Judaism and look

indistinguishable from their neighbors, though some—without

understanding exactly why—follow dietary laws that resemble

kashrut.

As for the Jewish expatriates I knew in

Beijing in 1980, there were barely enough of us to form a

minyan. On Yom Kippur, we gathered for makeshift services in

our suite overlooking the glazed tile rooftops of the

Forbidden City. Now, however, there are many Jewish

expatriate communities in China, and some educated Chinese

are even studying Hebrew, a practice which began in 1985,

when Beijing University first offered a Hebrew language

major. Simon Yu, a member of that class of eight, wanted to

learn more than the little available in high school history

books. “Friends thought it was strange that I was studying

Hebrew,” he acknowledges, “but now people think it’s very

charming and special.”

Simon Yu, an associate professor at the

Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences’ Center for Jewish

Studies, can speak Hebrew, but he cannot attend Jewish

services. Independent religion does not exist in China; even

the five sanctioned religions—Buddhism, Islam,

Protestantism, Roman Catholicism and Taoism—are controlled

by the government. (The Vatican, for example, does not fully

recognize Catholicism in China because, for one thing, China

refuses to cede authority over selecting bishops.) It is

hard to conceive of Judaism joining the ranks of

government-approved religions, considering, for instance,

that the government authorities do not allow Chinese

citizens to attend religious services led by outsiders.

One night at a Shabbat dinner at the home

of Rabbi Avraham Greenberg, his pregnant wife Nechama and

their two toddlers, I ask the bearded 26-year-old Israeli

rabbi whether Chinese ever show up at his services. “When I

arrived, my brother was already a rabbi here,” he says.

“After a local Chinese attended his service, the authorities

approached my brother, telling him to pack up and leave. But

he calmed them down by promising to turn away any such

‘visitors’ in the future. After that, a few tried, but my

brother asked them to leave.”

After five days in Beijing,

I board an overnight train bound for Shanghai. In my

sleeping compartment, I open River Town, Peter

Hessler’s memoir about teaching in China from 1996 to 1998.

I reach a passage in which Hessler is also on a train,

engrossed in a book. A woman approaches and comments on how

diligently he is working. “She peered at me,” he writes,

“and it was clear that she was thinking hard about

something. ‘Are you Jewish?’ she finally asked. ‘No,’ I

said, and something in her expression made me want to

apologize…. I sensed her disappointment as she returned to

her berth.”

How, then, to reconcile this reverence

for Jews with the appreciation for Adolf Hitler that Hessler

mentions elsewhere in his book? Hessler writes that

alongside “a deep respect for the Jewish people,” Chinese

appreciate the icon of Hitler mainly because of Charlie

Chaplain’s portrayal in The Great Dictator, which

many have seen multiple times. How are they able to overlook

that small matter of the Holocaust? For one thing, until

recently, it simply hadn’t been taught. For another, the

politically controlled Chinese educational system valued

rote learning and discouraged much independent thought. It

similarly trained Chinese to revere the revolutionary

Chinese leader Mao Zedong: At least a dozen educated Chinese

I ask for their view of Mao, give an identical answer, that

Mao was “70 percent good and 30 percent bad.” Even though

Mao had a major hand in substantially more deaths than

Hitler in the excesses of the Great Leap Forward and the

Cultural Revolution, this has been the Communist Party line

since 1981.

But this is changing: Fewer Chinese are

ignorant of the dark fate of many Jews of the last century.

In Shanghai, the port city to which many Jewish refugees

fled the Nazis, I meet Yang Peiming, an avid historian and

the proprietor of the Propaganda Poster Art Centre. He shows

me his private collection of 70-year-old passports that he

acquired at a local flea market. Each is stamped with

swastikas and a large red “J,” indicating it had belonged to

a European Jew who had made it to Shanghai, one of the few

shores open to these refugees. “Shanghai’s history cannot be

complete without Jewish history,” he tells me. “We learn

from Jewish people.”

Fudan Fuzhong, the

school where my daughter Emily teaches English conversation,

consists of low-rise dormitory and classroom buildings on a

lush campus. Today I am teaching a Jewish culture lesson to

five of Emily’s 12 weekly classes. The seeming identicalness

of these groups startles me: each a six-by-eight matrix of

10th-graders with shiny black hair, all wearing navy warm-up

suits trimmed in orange. Teachers rather than students are

the ones to move, so in every classroom 48 girls and

boys—some of China’s most promising—remain in the same tight

rows from 7:50 a.m. until 3:55 p.m. with breaks only for

physical education and lunch. Twice a day they do eye

exercises in their seats, five minutes of impassively

massaging around the eyes with fingertips per instructions

from a sing-song voice on the public address system. In the

evenings they return to their rows from 6:30 until 9:00 for

enforced study hall.

Emily had alerted me to the students’

reluctance to speak in class so, 15 minutes into the

40-minute session, I hand out paper and ask three questions

that I hope will spark discussion: What are your impressions

of Jewish people? Where did you get those impressions? What

questions do you have for us?

Throughout the week, I repeat this

lesson, which yields 576 responses. Around 90 percent of the

students write that Jews are clever, and approximately half

of those add that Jewish people are good at business. Though

the consensus is that Jews are rich, some who have seen the

Holocaust movie The Pianist say that Jews are poor.

A couple of perceptions of Jews as bullies come from

government-controlled TV news, during which reporters often

portray Palestinians as victims and refer to Israelis as

Jews, as though the two are interchangeable.

Some students question how Jewish people

feel about Germans today. A few want to know how you can

tell whether someone is Jewish. Several ask how they can get

“rich like the Jews,” including a boy who writes, “Jews own

50 percent of the wealth in America. How do they do this?”

There are numerous comments along the lines of: “Jews are

friendly, because Emily and Susan are friendly.”

The four-hour train ride to

Nanjing, a blur of browns and greens, is a welcome

contrast to Shanghai’s city skyline reconfigured daily by

lofty, dangling cranes. I had emailed the founder of Nanjing

University’s Institute for Jewish Studies, Xu Xin

(pronounced Shoo Shin), and asked what motivates Chinese

students to pursue Jewish studies. He invited me to visit,

suggesting a Friday so I could attend his undergraduate

Jewish culture class as well as meet his graduate students.

Xu Xin greets me in the hotel lobby. At approximately five

feet five inches, he walks with a light step in brown

leather Docksiders that seem more Nantucket than Nanjing.

“As a scholar of American literature, I

became interested in Jewish writers after Saul Bellow won

the Nobel Prize,” he explains in fluent English. In 1976, Xu

began researching Jewish American history and culture,

translating works of Norman Mailer, Clifford Odets and

others into Chinese and publishing articles such as “Jewish

Humor” and “The Image of the Schlemiel in Jewish

Literature,” in which he likens the schlemiel to the wise

fool in Chinese literature.

“In 1985 an American named James Friend

arrived here to teach literature for six months,” he

explains as we enter the 105-year-old university’s campus.

“I had never known a Jew before.” The two professors formed

a bond, and Friend invited Xu to live with his family and

teach at Chicago State University, where Friend was chairman

of the English department. While in the United States Xu

attended a bar mitzvah, seders and even Jewish funerals,

including that of Professor Friend, whose untimely death

from a heart attack occurred toward the end of Xu’s stay.

“My time with the Friends provided me

with a great opportunity to look at Jewish people,” says Xu.

He was impressed that Jews follow laws, rather than an

individual or just a set of beliefs. “Their way of living

and thinking made me aware that Jewish culture has many

lessons Chinese people could learn on their way to becoming

a responsible part of the international society.”

To that end, with one room and a few books, he created a

Jewish studies center at Nanjing University in 1992, shortly

after China and Israel established diplomatic relations.

Xu—who at age 18 was sent to the countryside during the

Cultural Revolution—was a pioneer; today at least ten other

academic institutions offer Judaic studies.

Xu leads the way into a tall, new

building and into an elevator which opens only a few steps

from a brass wall plaque that says Institute for Jewish

Studies in Chinese, English and Hebrew. “Each year we add

two M.A. and two Ph.D. students. And we try to provide a

scholarship for our Ph.D. candidates to study in Israel,”

explains Xu, motioning for me to follow him into the

library. The students want to understand, he says, how

Jewish culture has survived, indeed flourished, often in the

face of adversity. With a sweep of his arm, Xu shows off

more than 10,000 titles that range from Encyclopedia of

Midrash to Jewish Wit for all Occasions. The

stacks also hold volumes Xu has written or translated,

including an abridged version of the Encyclopedia

Judaica.

Down a spotless hallway is a conference

room where glass cabinets display assorted Judaica—a Kiddush

cup, a tallit, a small Torah—evoking the quiet ambience of

an upscale temple gift shop. Professor Song Lihong and six

of the program’s 12 graduate students are waiting for us.

After easing into a chair at the head of the long,

rectangular table, Xu leans forward and folds his hands in

front of him. “Once Western studies became part of the

curriculum in Chinese universities,” he says, “in

literature, philosophy, science—inevitably you came across a

Jewish name.” He notes the disproportionate number of Jewish

Nobel Prize recipients and adds, “You don’t see that many

Norwegians with Nobel Prizes.”

Xu seems to delight in the shared aspects

of our two cultures, saying, “Both have had a great impact

in the world, both have suffered and in both cases, parents

do anything they could to give their children better

education. Jewish and Chinese are the only major cultures to

retain their traditions unbroken for thousands of years.”

We board a crowded bus

that takes us across the Yangtze River to a satellite campus

for Xu’s freshman Jewish Culture class. He tells me that I

will be the first Jew most of the undergraduates have ever

met.

In the spacious classroom, Xu introduces

me and hands me the microphone and the 100 students applaud

vigorously. They then become utterly silent, riveted before

I say a word. In English, I tell them about my semi-secular

style of Judaism, a slice of life unlikely to show up in

their textbooks. They seem to follow, smiling appropriately

when I mention my teenage struggle with my father, who

forbade me to date a non-Jewish football player from my

school. Their attention is so focused that I wonder if they

are scrutinizing me to figure out what distinguishes my

Jewishness. Forty-five minutes later, I invite them to ask

questions.

A slender girl wearing glasses and a

ponytail approaches and says, “The biggest difference

between Chinese and Jewish culture is that you believe in

religion.” I ask about Confucius, and she answers, “He was

an educator, not in your heart.” Another adds, “For us,

spirituality does not exist.”

Later on, at a nearby restaurant. I sit

beside Professor Song, a.k.a. Akiba, at the round table

where Moshe, Yam, Gal, Omer and Alon, the graduate students

I met earlier, have already gathered. Just as the Chinese

infatuation with the West has led many to take English

names, these students have assumed Hebrew names.

The bespectacled Akiba, uses his

chopsticks to place a mound of spicy pork with vegetables on

my plate. “We don’t have Judeophobia, we have Judeophilia,”

he says with a smile. It was the Roman historian and

warrior, Flavius Josephus, who inspired his interest in

Jewish studies. “There were many renegade Chinese; Josephus

was the first renegade Jew I discovered,” he explains.

The students join in, explaining the

origins of their fascination. One student tells me that she

“became interested because of a special year, 135 A.D., when

most of the people left Palestine and began diaspora. In

spite of anti-Semitism, the Jewish people survived and kept

their traditions.” Another is interested in the parallels

between the Holocaust and the Nanjing massacre, during which

Japanese troops killed as many as 300,000 Chinese, including

thousands of women and children. Akiba adds, “The Japanese

still have not pled guilty to this crime. In Germany the

president knelt at Auschwitz; this is a sharp contrast.”

As I survey the table, it’s evident how

comfortable these students are in sharing their passion for

Judaism. And though each has a different focus, I am struck

that I am witnessing such a deep appreciation of Jewish

culture.

I think of a remark Xu made earlier that

although he is proud of the similarities that Chinese

culture shares with Jewish culture, he believes Jews have

exceeded the Chinese in one valuable quality: Morality. He

cited the pirated DVDs sold openly on China’s streets as an

example of shamelessness that he finds all too prevalent in

his country. I suggested that Xu’s conception of Jews might

be a tad idealistic, since I imagined that I myself would

willingly buy such DVDs—though I admitted I would feel

guilty. “When you buy, you feel guilty,” Xu told me. “You

have this moral sense; when Chinese buy it, they never feel

guilty. That’s the moral challenge.” He grew solemn and,

with the conviction of a rabbi, added, “We could learn to

achieve a moral society from Jewish people.”

The day winds down and we emerge into the

humid air. The aroma of fresh fruit wafts from the back of a

faded green pickup truck where students have lined up to buy

whole neatly peeled pineapples for around 30 cents apiece.

Back at the main campus, I walk with Xu to his bicycle along

a tree-lined path. It is the end of the workweek, and a

teacher heading the other way nods and says, “Ni hao.

Shabbat shalom.”

|