Coat Bomb and Explosive Prosthesis: British Intel Files Reveal How the Zionist Stern Gang Terrorized London

MI5's dossiers on the group released this week cast the Cold War's early years in a stark new light: Terrorism, not the Soviet Union, was the main threatBy Calder Walton

Ha'aretz, December 2, 2017

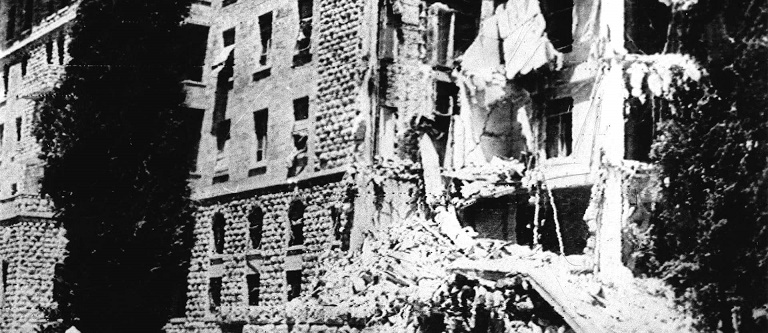

The wrecked wing at the King David hotel where the British government chief secretary's office was located, immediately after the

explosion, Jerusalem, July 22, 1946.

Credit: AP

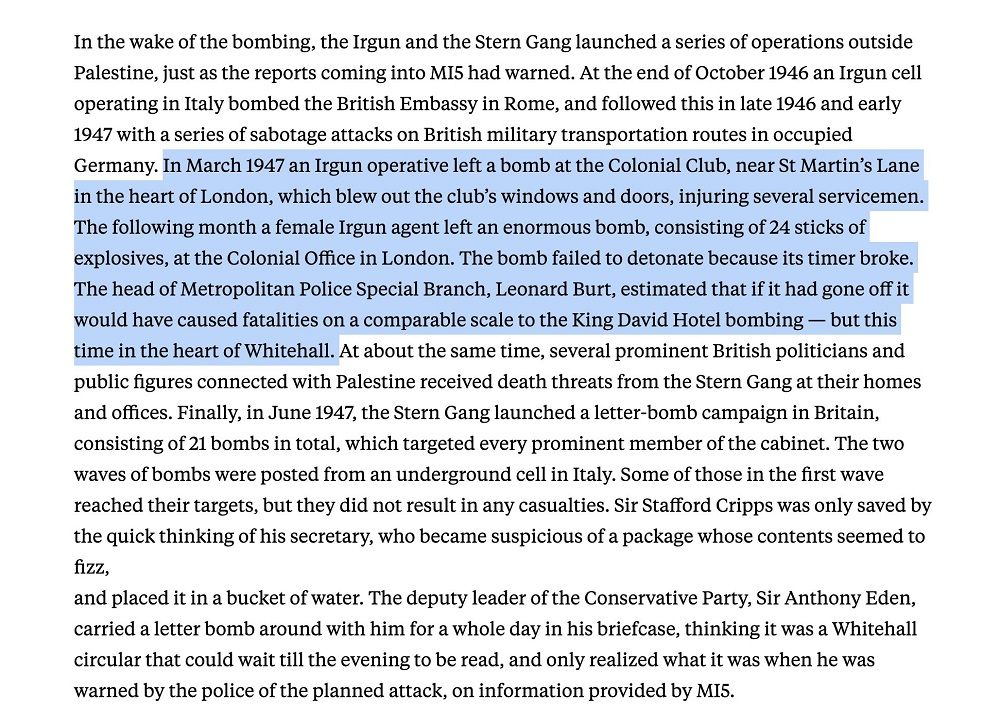

Records declassified this week by Britain’s Security Service, MI5, reveal an urgent terrorist threat that Britain faced in the 20th century. No, it wasn’t the Irish Republican Army or Islamist terrorist groups that would plague Britain later in the century, but rather extremist Zionist groups fighting the British after World War II to establish the State of Israel.In July 1946, one of these groups, the Irgun, led by the future Israeli prime minister and Nobel Peace Prize winner Menachem Begin, blew up the headquarters of the British administration in Palestine, Jerusalem’s King David Hotel, with heavy loss of civilian life and damage. The newly released MI5 files show that another group fighting the British, the Lehi or “Stern Gang,” dispatched cells to carry out bombings and assassinations in Britain itself. The Stern Gang is thought to be the world’s last terrorist group to describe itself publicly as “terrorist,” with some of its members using the term as a badge of honor.

In April 1947, two Stern Gang terrorists, a man and a woman, attempted to blow up the Colonial Office in Whitehall in the center of London. They planted a bomb containing 24 sticks of explosives at Dover House, headquarters of the Colonial Office, but it failed to go off because it was not fused correctly. The head of London’s Special Branch, commander Leonard Burt, believed that if the bomb had gone off, it would have caused as much damage as the bombing of the King David Hotel in London nine months earlier.

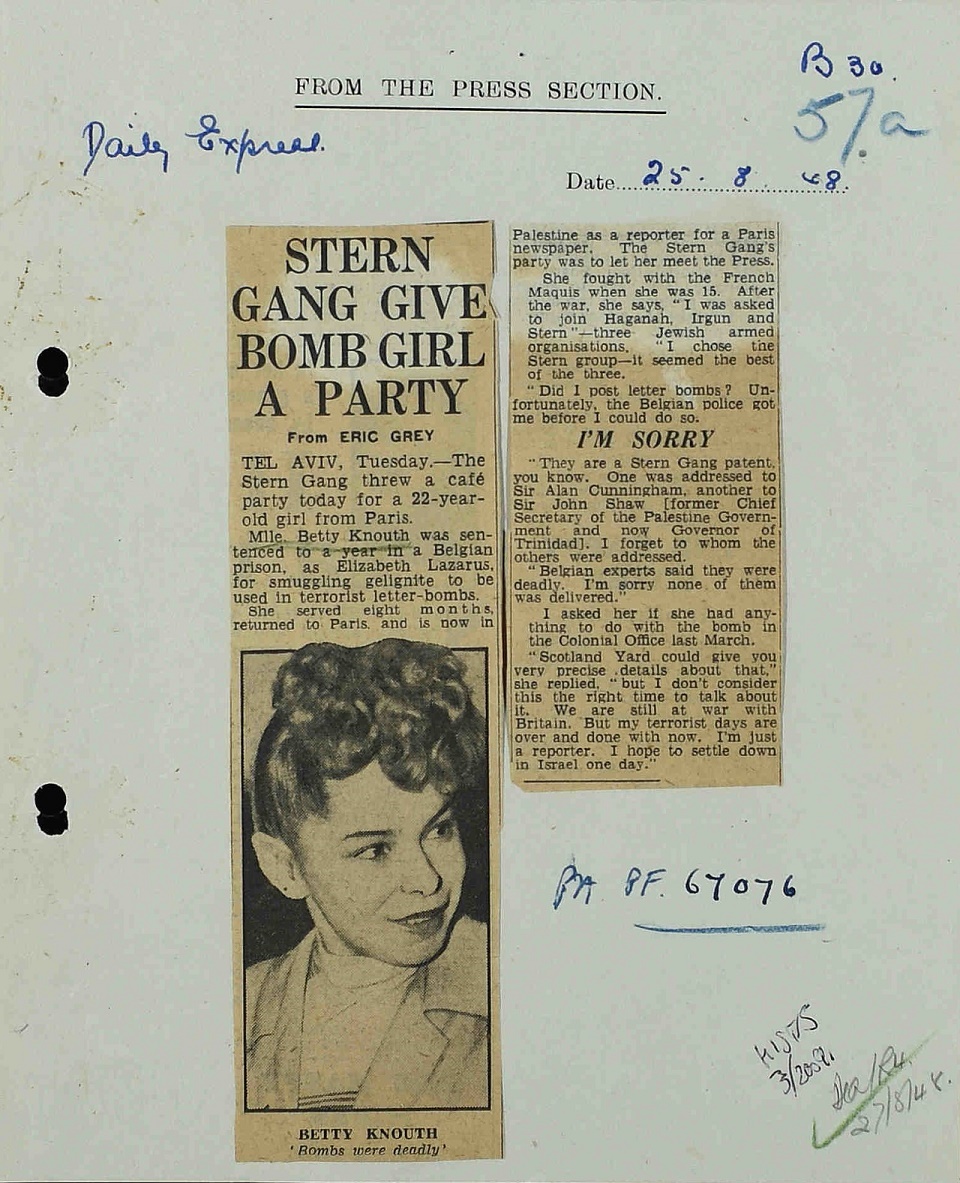

A cut out from the Daily Express, August 25, 1948.

Credit: Britain's Security Service Archive

The Stern Gang’s attempted bombing of the Colonial Office in London has been previously revealed. But the files released this week are the first public records from British intelligence’s secret archives to show how the Stern Gang operators were tracked down. They also reveal significant new facts about the plot and aspects of it that apparently MI5 did not detect.In June 1947, two months after the attempted bombing of the Colonial Office, a Stern Gang cell operating in Italy posted 21 letter bombs to senior British politicians and cabinet members including Prime Minister Clement Attlee, Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin and Chancellor of the Exchequer Stafford, Cripps as well as Winston Churchill. Most of the letter bombs were intercepted, but some reached their intended recipients and failed to go off.

The Conservative Party’s Anthony Eden carried a letter bomb disguised in a book around with him for a whole day, until he was warned of the plot and checked inside his briefcase, where it was. British explosive experts reported that all the letter bombs were potentially lethal. One Stern Gang member involved in the plot later claimed that he had “invented the book bomb.”

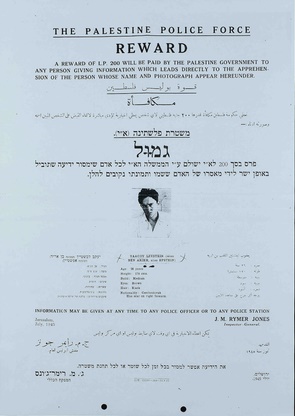

A Palestine Police Force poster requesting information.

Credit: Britain's Security Service Archive

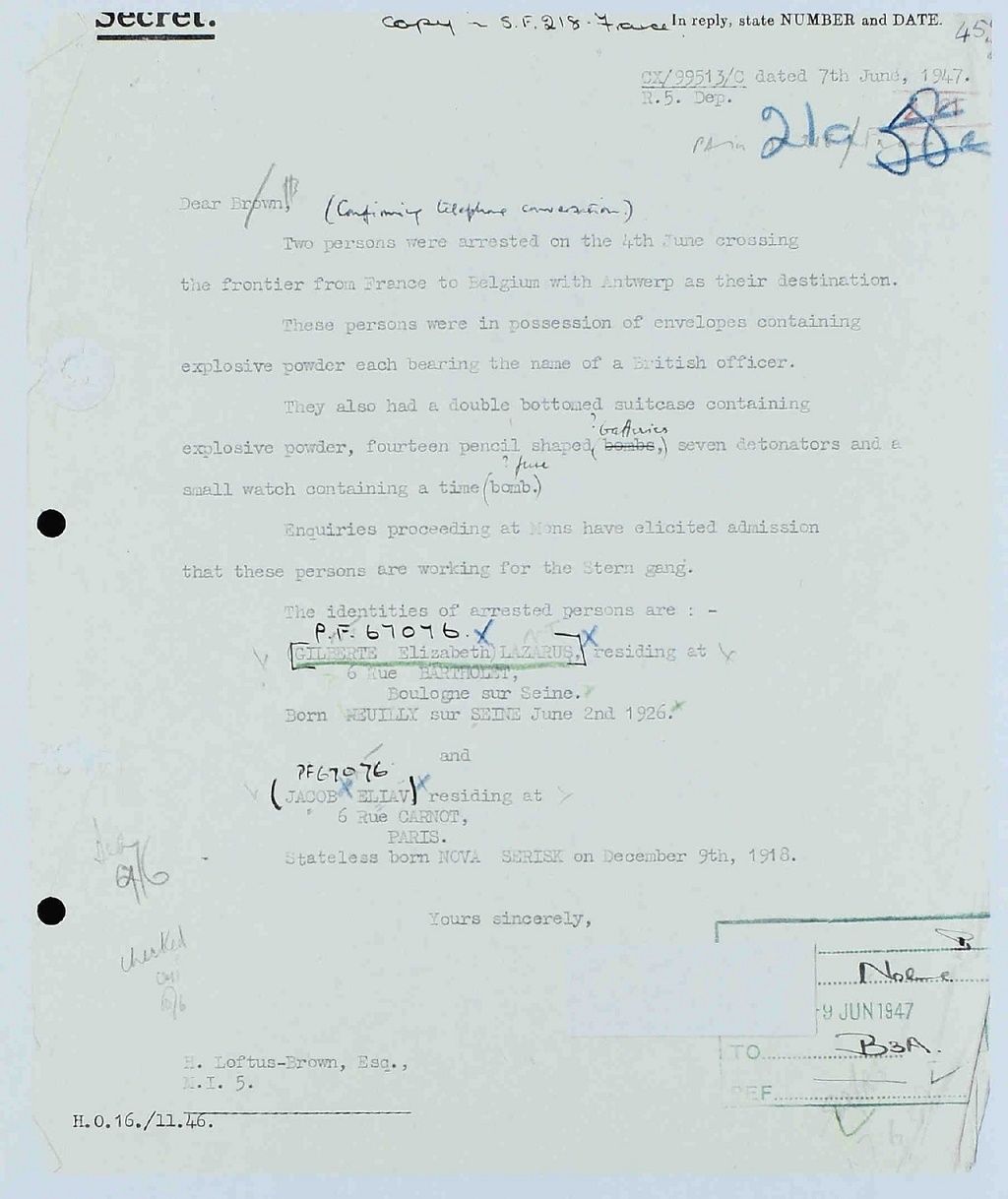

French-Belgian border check

In the wake of the Colonial Office and letter bombs, borders and ports in Britain were placed on high alert to look for suspicious people potentially planning further attacks, and MI5 placed known extremist Jewish and Zionist groups in Britain under intense surveillance. But as one MI5 officer wrote in an internal memo, “these terrorists are hard nuts to crack.”

In a routine inspection that same month, June 1947, Belgian police stopped and searched two people, a man and a young woman, at the border crossing to France. The woman’s suitcase was found to have a false bottom with a secret compartment. It contained letters addressed to British officials, together with explosives, 14 pencil-type batteries, seven detonators and a watch constructed as a time fuse — similar to the letter bombs sent earlier that month and the bomb rigged up at the Colonial Office.

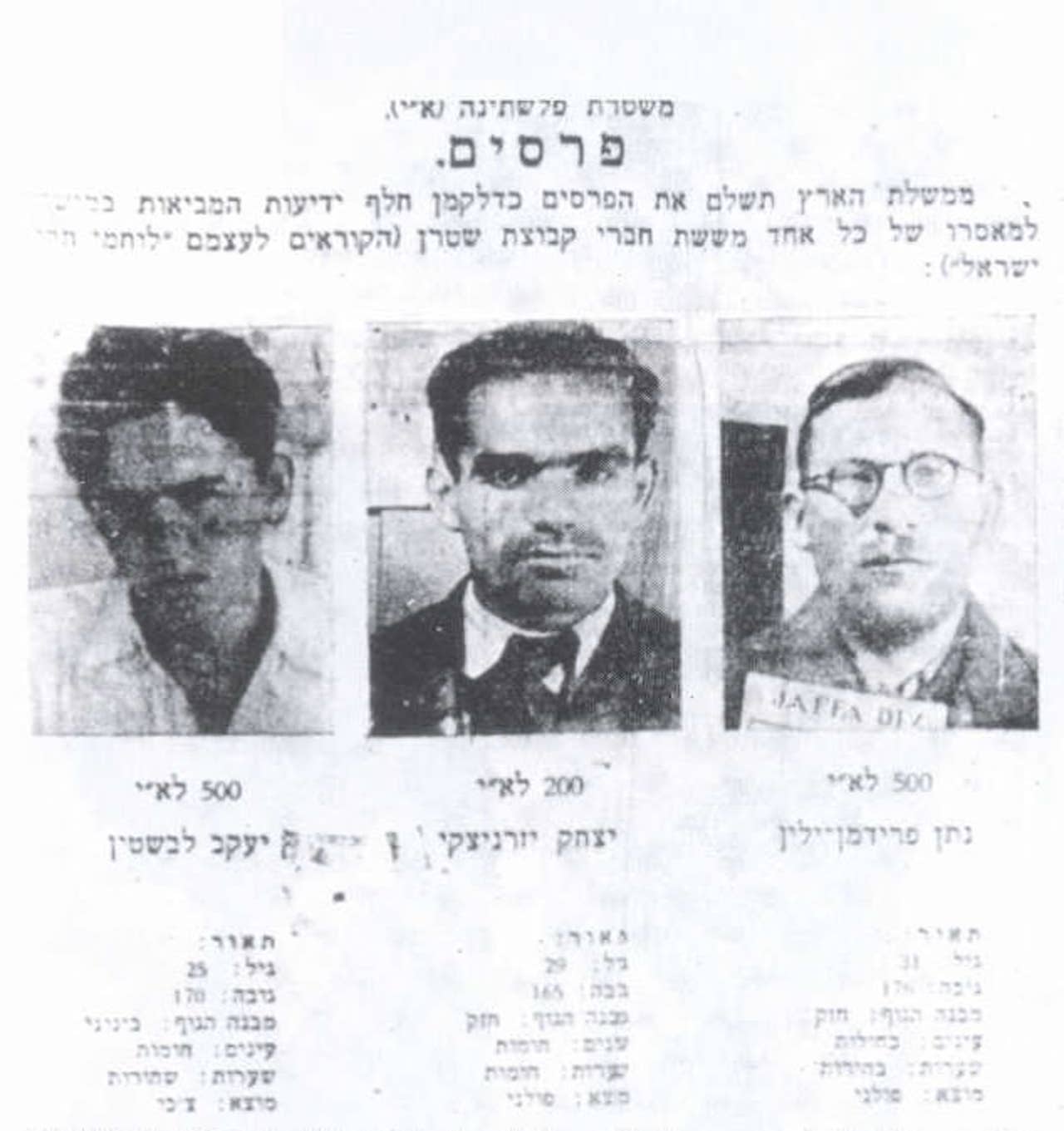

A wanted poster of the Palestine Police Force during the 1920-48 Mandate period: Lehi members

Yaacov Levstein, left, Yitzhak Shamir and Natan Yellin-Mor.

Credit: Palestine Police Force

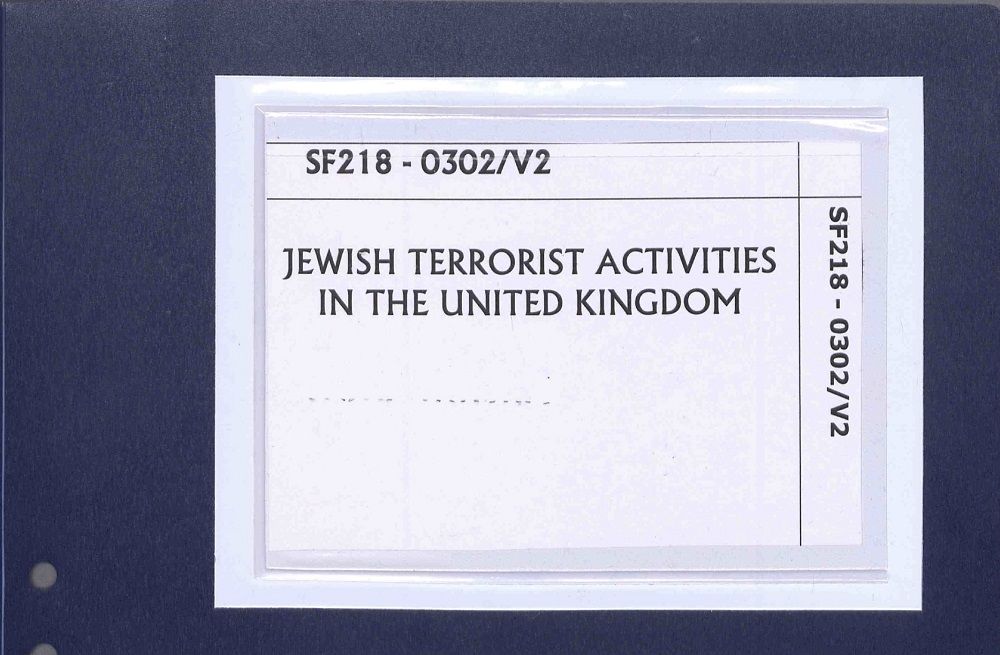

The man and woman were arrested by the Belgian police, who, because of the envelopes addressed to British officials, contacted the British authorities. It didn’t take MI5 long to conclude that the pair had been planning to carry out bomb attacks in Britain. One of the letters, soon to be a letter bomb, was addressed to the chief secretary of the Palestine Administration, Sir John Shaw, who later secretly worked for MI5.The arrested 22-year-old woman was identified as Betty Knouth, who also went under the name Gilberte Elizabeth Lazarus. She was a French national who had served with the Resistance during the war and was now, as she put it, at war with Britain. She was sentenced to a year in prison in Belgium for carrying explosives.

Checking its records, MI5 quickly discovered that Knouth fitted witness descriptions of an attractive young woman seen at the Colonial Office when the bomb was left, carrying a distinctive blue-leather miter-shaped handbag, which was still in her possession when she was arrested in Belgium. Knouth also admitted to being in Britain at the time of the Colonial Office bomb.

The arrested man went under the name Jacob Elias, but when his fingerprints were sent to London, his real identity was established as Yaacov Levstein, who had a long track record as a terrorist. His named appeared on the “Terrorist Index” compiled and circulated by the Palestine police and MI5.

The letter alerting British authorities of the Stern Gang members' arrest on the French-Belgium border, June 7, 1947.

Credit: Britain's Security Service Archive

Levstein had been a member of the Stern Gang throughout the war, and was wanted by the Palestine police for his believed killing of numerous police officers and an attempt on the life of the British high commissioner. He had been captured and sentenced to life imprisonment in Palestine, but escaped from jail. His fingerprints matched those found on the timer of the failed bomb at the Colonial Office. He was given eight months in prison in Belgium for carrying concealed explosives.

A newspaper cutout referring to Stern Gang Member Betty Knouth, who also went by the name Gilberte Elizabeth Lazarus.

Credit: Britain's Security Service Archive‘We are still at war with Britain’

At a Stern Gang press conference in Tel Aviv after her release from jail, Knouth said in response to a question: “Did I post letter bombs? Unfortunately the Belgian police got me before I could do so. They are a Stern Gang patent you know.”

Asked if she had anything to do with the bomb left at the Colonial Office, she said: “Scotland Yard could give you very precise details about that, but I don’t consider this the right time to time to talk about it. We are still at war with Britain. But my terrorist days are over and done with now. I hope to settle down in Israel one day.”

Britain’s intelligence records released this week reveal that MI5 did not detect some terrorist operations. The files note that Levstein was an “expert in explosives” but do not grasp the true devilish nature of his expertise. The files correctly record that a French veteran associated with Levstein, Jacques Martinsky, was denied entry when he landed in London in March 1947 for showing no good reason why he was traveling to Britain.

However, MI5 appears not to have detected that, on Levstein’s instructions, Martinsky was using the prosthetic leg that he acquired after being wounded in the war to smuggle explosives into Britain for the Colonial Office bomb. This was a lucky escape for British security.

Where Martinsky failed, another of Levstein’s group got through. As Levstein later explained, he succeeded in getting explosives for the Colonial Office bomb into Britain by devising an ingenious “coat bomb” with explosives stitched inside. It was worn by another of his accomplices, Robert Misrahi, a French student and protégé of Jean-Paul Sartre at the Sorbonne who carried this dynamite coat from Paris across the Channel to Britain.

The new files show that Misrahi’s name was on MI5’s radar, but there is no evidence that the security service detected the plot. As Levstein later put it: “The execution was perfect. I learned an important lesson. No security measures can stop sophisticated imaginative planning.”

Victory parade in London, June 8, 1946.

Credit: Ministry of Information Photo Division / Wikimedia Commons

MI5’s dossiers on Stern Gang members released this week cast the early years of the Cold War in a stark new light — terrorism, not the Soviet Union, was the main threat. The newly released files also have an enduring legacy. Many of the security techniques British intelligence developed to deal with the Irgun and Stern Gang — surveillance of extremist groups, border and port checks, liaison with foreign police agencies — were the same counterterrorist procedures later used against the IRA and current Islamist terror groups.

Calder Walton is an Ernest May Fellow at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. His book “Empire of Secrets: British Intelligence, the Cold War and the Twilight of Empire” was published by Harper Press in 2013. Follow him on Twitter @calder_walton.

Addendum:

Wise words on Jewish terror vs. the UK, by Professor David Miller:Posted on X, Oct 3, 2024

I am asked by Islamophobic Zionists: "How many Jews/Zionists set off bombs in UK buses/Tubes"?The answer is: quite a few tried. Some succeeded. Revisionist Zionists conducted a campaign of terror against British targets in Palestine, Germany, Italy, Egypt and in the UK in the 1940s.

In the UK specifically, here is a summary.

The Stern Gang invented the book bomb and used it for the first time in the UK to attempt to kill Major Roy Farran in Wolverhampton. They killed his brother Rex instead. The bomb was inside a hollowed out copy of Shakespeare's plays.

They also tried to kill many of the Cabinet with 21 letter bombs targeting every prominent member of the Cabinet including Prime Minister Clement Atlee, Stafford Cripps, and Sir Anthony Eden.

The Irgun also bombed the Colonial Club and planted a bomb at the Colonial Office which failed to detonate.

MI5 released two thick files on this activity a few years ago. Here is the cover of one of the files.

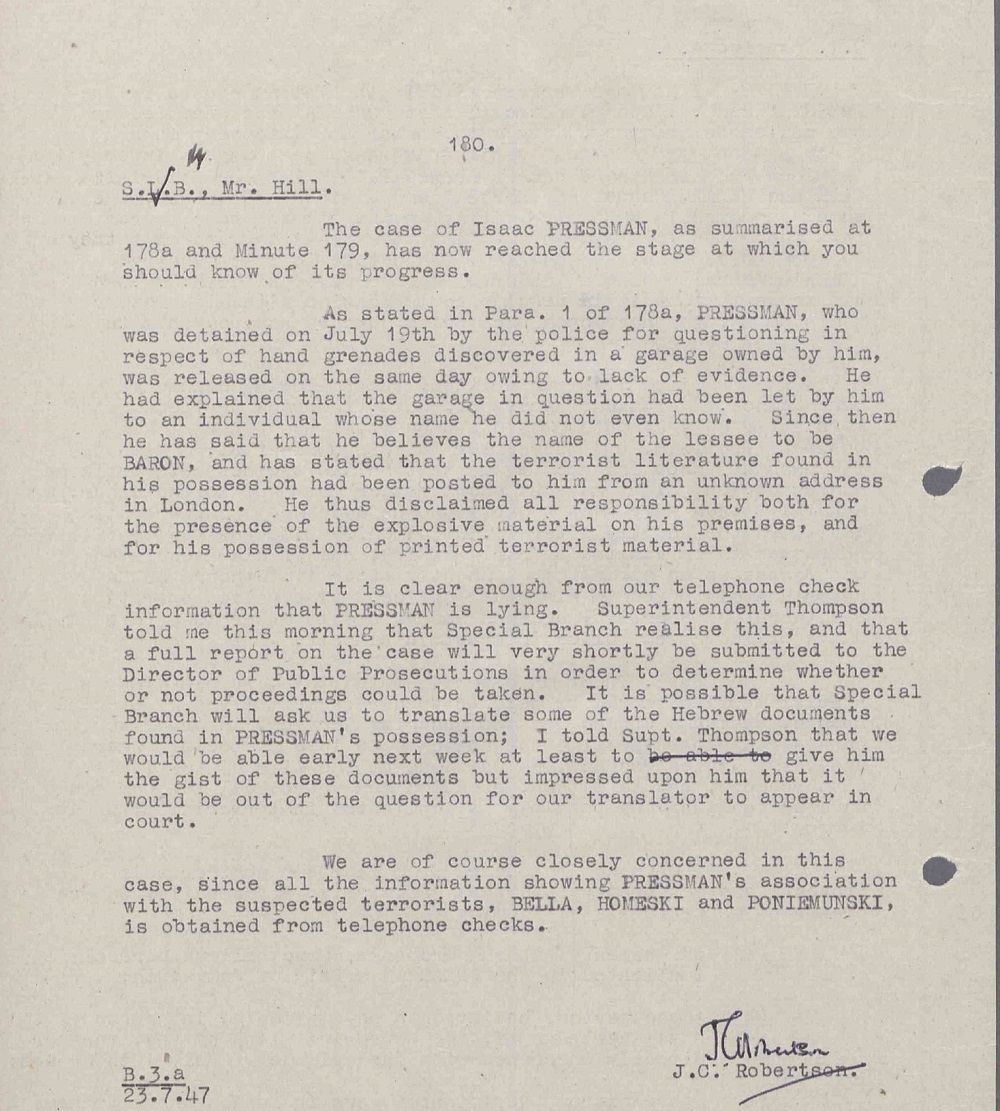

They had significant numbers of operatives and supporters throughout the UK (including in Scotland) and though many of them came to the attention of Special Branch and MI5, (their names are recorded in the now declassified MI5 files) hardly any were charged or even arrested.Here is an account from the MI5 files of 1947 of an Irgun cell who were storing explosives and other terrorist materials and were questioned but none of them was ever even arrested, never mind jailed. Two key Irgun operative Isaac Pressman and Leo Bella were involved. As you can see the presence of the Irgun literature and the 24 grenades and 24 detonators were explained away. Pressman insisting that he had rented out the garage concerned had no knowledge of the weapons.

So, have Zionists ever plotted and carried out terror attacks in the UK? Yes.

Would they do so again? A question for all UK citizens to ponder.

|

Races? Only one Human race United We Stand, Divided We Fall |

|

No time to waste. Act now! Tomorrow it will be too late |

|