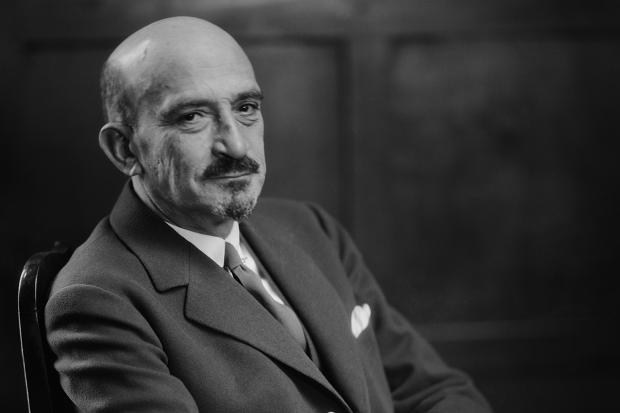

*Dr Chaim Weizmann, President of the World Zionist Organisation and the Jewish Agency for Palestine, 1921–31 and 1935–46; President of the State of Israel, 1949‑52.

Secret Soviet Reveals: Weizmann outlined the Nakba as early as 1941By Gilad Atzmon

Whatsupic, 26 June 2014

Forthcoming in G. Gorodetsky (ed.), A Red Ambassador to the Court of St. James’s: The Diaries of Ivan Maisky, 1932-43.

Introduction by Gilad Atzmon

The following is a unique historical document. It is an extract from The Diaries of Ivan Maisky, the Soviet Ambassador to Britain from 1932 to 1943. As far as I am aware this is the debut online appearance of this invaluable document.Ivan Maisky (second from left), the Soviet ambassador to London between 1932 and 1943, with Winston Churchill at the Allied ambassadors’ lunch at the Soviet embassy, September 1941. General Władysław Sikorski, prime minister of the Polish government in exile, is second from right.

Maisky, a former Menshevik of Jewish origin, kept a highly personal diary. He recorded conversations with five British prime ministers, as well as with many other prominent British politicians.

In this extract, written on 3 February 1941, Maisky recounts his brief meeting with the Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann, later the first president of Israel. Maisky provides crucial insights into the history of Zionism including the brutality of the Jewish plan for Palestine and the Middle East. Noticeably, the document reveals that an intention to expel the Palestinians was explored by Zionist leaders as early as 1941.

Chaim Weizmann

Weizmann begins the meeting with a business plan. “Weizmann came to discuss the following matter,” says Maisky, “at present Palestine has no market for her oranges – would the USSR take them in exchange for furs? It would be easy to sell the furs through Jewish firms in America.” Establishing a Jewish nation is a cheerful event, but it is even better if one can earn some shekels on the side. Clearly, even in 1941, Zionism saw itself as part of a global financial venture.

Weizmann was clearly troubled by ‘the English’. “The English” Weizmann complains, “don’t like Jews.” While the “Palestinian Arabs are the kind of guinea pigs the (British) administrator is used to,” Says Weizmann. “The Jews reduce him to despair. They are dissatisfied with everything, they ask questions, they demand answers …But the main thing is that the administrator constantly feels that the Jew is looking at him and thinking to himself: “Are you intelligent? But maybe I’m twice as intelligent as you.”

Those who believe that the racially driven expulsion of the Palestinians from their land in 1948 was the result of a series of tragic events, can discover from Maisky’s diary that in 1941 an ethnic cleansing plan had already been outlined. Maisky writes in his diary: “For the only ‘plan’ which Weizmann can think of to save central European Jewry (and in the first place Polish Jewry) is this: to move a million Arabs now living in Palestine to Iraq, and to settle four or five million Jews from Poland and other countries on the land which the Arabs had been occupying.”

“I expressed some surprise about how Weizmann hoped to settle five million Jews on territory occupied by one million Arabs,” Maiky writes.

“’Oh, don’t worry’, Weizmann burst out laughing. ‘The Arab is often called the son of the desert. It would be truer to call him the father of the desert. His laziness and primitivism turn a flourishing garden into a desert. Give me the land occupied by a million Arabs, and I will easily settle five times that number of Jews on it.’”

It is painful that this ethno-centric approach prevailed. Seven years after this intimate meeting in London, the new Israelites expelled the vast majority of the Palestinians. Those Palestinians and their descendants remain dispossessed and many of them are forced to live in refugee camps in the region. Those who managed to evade expulsion were then and continue to be subject to Israeli racial discrimination and daily abuse.

————— ————— ————— —————

Forthcoming in G. Gorodetsky (ed.), A Red Ambassador to the Court of St. James’s: The Diaries of Ivan Maisky, 1932-43.

3 February 1941

A few days ago I had an unexpected visitor: the well-known Zionist leader Dr. Weizmann. He is a tall, elderly, elegantly dressed gentleman with a pale yellow tinge to his skin and a large bald patch on his head. His face is very wrinkled and marked by dark blotches of some kind. His nose is aquiline and his speech calm and slow. He speaks excellent Russian, although he left Russia forty-five years ago.

President Harry S. Truman and Israeli President Dr. Chaim Weizmann. Truman is holding a blue velvet mantle embellished with the Star of David. The mantle was a gift symbolizing Israel's gratitude for American recognition of and support for the new nation.

Weizmann came to discuss the following matter: at present Palestine has no market for her oranges – would the USSR take them in exchange for furs? It would be easy to sell the furs through Jewish firms in America.

I answered Weizmann by saying that off hand I could not say anything definite, but I promised to make enquiries. However, as a preliminary reply, I said that the Palestinian Jews should not place any great hopes on us: we do not, as a rule, import fruit from abroad. I was proved right. Moscow turned down Weizmann’s proposal, and I sent him a letter to that effect today.

In the course of the conversation about oranges, Weizmann talked about Palestinian affairs in general. Furthermore, he spoke about the present situation and the prospects for world Jewry. Weizmann takes a very pessimistic view. According to his calculations there are about 17 million Jews in the world today. Of these, 10-11 million live in comparatively tolerable conditions: at any rate, they are not threatened with physical extermination. These are the Jews who live in the US, the British Empire and the USSR. Weizmann spoke about Soviet Jews in particular: ‘I’m not worried about them. They are not under any threat. In twenty or thirty years’ time, if the present regime in your country lasts, they will be assimilated.’

‘What do you mean, assimilated?’ I retorted. ‘Surely you know that Jews in the USSR enjoy all the rights of a national minority, like the Armenians, Georgians, and Ukrainians and so on?’

‘Of course I know that’, Weizmann answered, ‘but when I say “assimilated”, all I mean is that Soviet Jews will gradually merge with the general current of Russian life, as an inalienable part of it. I may not like this, but I’m ready to accept it: at least Soviet Jews are on firm ground, and their fate does not make me shudder. But I cannot think without horror about the fate of the 6-7 million Jews who live in central or south-eastern Europe – in Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, the Balkans and especially Poland. What’s going to happen to them? Where will they go?’

Weizmann sighed deeply and continued:

‘If Germany wins the war they will all simply perish. However, I don’t believe that the Germans will win. But even if England wins the war, what will happen then?’

Here he began to set out his fears. The English – and especially their colonial administrators – don’t like Jews. This is particularly noticeable in Palestine, which is inhabited by both Jews and Arabs. Here the British ‘high commissioners’ undoubtedly prefer the Arabs to the Jews. Why? For one very simple reason. An English colonial administrator will usually get his training in British colonies like Nigeria, the Sudan, Rhodesia and so on. These places have a well-defined pattern of rule: a few roads, some courts, a little missionary activity, a little medical care for the population. It’s all so simple, so straightforward, so calm. No serious problems, and no complaints on the part of the governed. The English administrator likes this, and gets used to it. But in Palestine?

Growing more animated, Weizmann continued:

‘You won’t get very far with a program like that here. Here there are big and complex problems. It’s true that the Palestinian Arabs are the kind of guinea pigs the administrator is used to, but the Jews reduce him to despair. They are dissatisfied with everything, they ask questions, they demand answers – and sometimes these answers are not easily supplied. The administrator begins to get angry and to see the Jews as a nuisance. But the main thing is that the administrator constantly feels that the Jew is looking at him and thinking to himself: “Are you intelligent? But maybe I’m twice as intelligent as you.” This turns the administrator against the Jews for good, and he begins to praise the Arabs. Things are quite different with them: they don’t want anything and don’t bother anyone.’

And then, taking all these circumstances into account, Weizmann anxiously asks himself: ‘What has a British victory to offer the Jews?’ The question leads him to some uncomfortable conclusions. For the only ‘plan’ which Weizmann can think of to save central European Jewry (and in the first place Polish Jewry) is this: to move a million Arabs now living in Palestine to Iraq, and to settle four or five million Jews from Poland and other countries on the land which the Arabs had been occupying. The British are hardly likely to agree to this. And if they don’t agree, what will happen?

I expressed some surprise about how Weizmann hoped to settle five million Jews on territory occupied by one million Arabs.

‘Oh, don’t worry’, Weizmann burst out laughing. ‘The Arab is often called the son of the desert. It would be truer to call him the father of the desert. His laziness and primitivism turn a flourishing garden into a desert. Give me the land occupied by a million Arabs, and I will easily settle five times that number of Jews on it.’

Weizmann shook his head sadly and concluded: ‘The only thing is, how do we obtain this land?’

Gilad

Atzmon is an Israeli-born British jazz saxophonist,

novelist, political activist and writer.

Gilad

Atzmon is an Israeli-born British jazz saxophonist,

novelist, political activist and writer.