Israel, U.S. Still Battle for Lebanon’s Litani River Water

By Andrew I. Killgore

Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, September 2003, page 20

In 1955 President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent Eric Johnston,

president of the Motion Picture Producers’ Association, to the

Middle East to “divvy up,” in the phrase of the day, the water of

the Litani River. The Arabs could not make the political decision to

divide the Jordan River with Israel, but getting a decision from

Israel on the exact amount of water it claimed to have coming was

impossible.

Johnston finally realized that Israel was claiming more cubic feet

per second (cusecs) than the total flow of the river. Israel

buttressed its claim by citing the Cotton Plan, named for a

never-quite-identified American hydrologist. It turned out that

“Cotton” had combined the flow of the Jordan and the Litani rivers

to come up with Israel’s share. The Litani of course, flows entirely

in Lebanon.

At the 1919 Peace Conference in Paris, ending World War I, Chaim

Weizemann and David Ben-Gurion, respectively first president and

first prime minister of Israel, presented a proposed map of the

Israel that-was-to-be that included the Litani River within Israeli

borders. The Litani did not go to Israel, however, because under the

terms of the secret Sikes-Picot Treaty it was assigned to what would

be the French Mandate of Lebanon.

Iran begins to come into the picture when it changed from a friend

to an enemy of Israel. In 1978-1979 Muhammad Reza Shah Pahlavi was

overthrown, to be replaced by an Islamic regime under the Ayatollah

Ruhollah Khomeini, marking the end of a quiet alliance between

Israel and Iran. In 1978 Israel—anticipating a new government in

Tehran that would support its fellow Shi’i in southern

Lebanon—invaded and occupied its northern neighbor up to the Litani

River.

In 1982 Israel again invaded Lebanon to drive out the Palestine

Liberation Organization and to establish a government in Beirut that

would allow Israel to exploit the Litani. The war, engineered by

Israel’s then-Minister of Defense Ariel Sharon, resulted in the

death of 20,000 Lebanese, 2,000 Palestinians massacred in the Sabra

and Shatila refugee camps, and the evacuation from Lebanon of the

PLO.

The Israeli army slowly retreated from Lebanon under continued

harassment from the country’s long-neglected Shi’i—who had

originally welcomed them in 1978 as a counter to the Palestinian

presence there, but who soon turned against them upon exposure to

the occupiers’ contempt and hatred for the Lebanese. The resistance

organization Hezbollah, in fact, was founded in 1982 under the

guidance of Iran’s ambassador to Syria Ali Akbar Mohtashemi. Israel

did not fully withdraw from Lebanon until 2000, however, having

retained a slice of Lebanon up to the Litani for more than two

decades.

The United States gradually began economic warfare on Iran because

of Tehran’s continued assistance to Hezbollah. In 1994 Israel

claimed that an Iranian military buildup threatened Western

interests. Two years later President Bill Clinton issued an

executive order imposing sanctions on Iran. In 1996 Congress passed

the Iran-Libya Sanction Act (ILSA), written by the American Israel

Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) and providing for U.S. sanctions

against any company—foreign or domestic—spending $20 million on

Iran’s oil or gas industry. Russia’s Gasprom, French (then) Total

and Malaysia’s Petronas challenged ILSA by contracting to develop

Iran’s offshore South Pars gas field for billions of dollars.

President Clinton met with his top advisers and decided to take no

action, in effect accepting that ILSA was unenforceable.

Nevertheless Congress extended it in 2001 for five more years.

Perhaps the most successful effort to stymie Iran’s development,

however, is the effort to block oil or gas lines from the Caspian

from going through Iran. Oil companies operating in the Caspian

favored the Iranian route, but the U.S.—and Israel—decided that it

had to be Baku (Azerbaijan)-Ceyhan (Turkey).

The latest manifestation of Washington’s relentless economic warfare

against Iran to pressure it to abandon its support of Hezbollah is a

recent high-level approach to Japan saying that Tokyo’s relationship

with the U.S. will suffer if it signs an agreement to develop part

of Iran’s largest oilfield, Azadegan. According to the June 28-29

Financial Times, Azadegan was viewed in Japan as a vital source of

long-term energy supply after Japan lost the rights to pump crude

oil from Saudia Arabia’s Kafgi area two years ago.

Supposedly the U.S. is exercised by Iran’s “suspected” nuclear

weapons program, although Thomas Stauffer writes (see p. 28) that it

is highly unlikely that it has a program to make the bomb. The U.S.

wants Tehran to sign an agreement allowing “intrusive” inspections

of its nuclear facilities.

National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice has spoken with top

Japanese officials; Secretary of State Colin Powell raised the issue

with Japanese Foreign Minster Yoriko Kawa Guchi. The United States

doesn’t want Japan to send the “wrong message.” Japan’s minister for

economy, trade, and industry was said to be resisting American

pressure, but Prime Minster Junichiro Koizumi was seen as

susceptible to U.S. pressure.

Andrew Killgore is publisher of the Washington Report on

Middle East Affairs.

"When a Jew, in America or in South Africa, talks to

his Jewish companions about 'our' government, he means the

government of Israel."

- David Ben-Gurion, Israeli Prime Minister

Viva Palestina!

Latest Additions

- in English

What is this Jewish

carnage

really about? - The background to

atrocities

Videos on Farrakhan, the Nation of Islam and Blacks and Jews

How Jewish Films and Television Promotes bias Against

Muslims

Judaism is Nobody's

Friend

Judaism is the Jews' strategy to

dominate non-Jews.

Jewish War Against

Lebanon!

Islam and Revolution

By Ahmed Rami

Hasbara -

The Jewish manual

for media deceptions

Celebrities bowing to their Jewish masters

Elie Wiesel - A Prominent False Witness

By Robert Faurisson

The Gaza atrocity 2008-2009

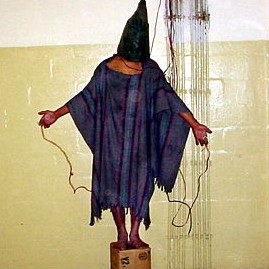

Iraq - war and occupation

Jewish War On

Syria!

CNN's Jewish version of "diversity"

- Lists the main Jewish agents

Hezbollah the Beautiful

Americans, where is your own Hezbollah?

Black Muslim leader Louis Farrakhan's Epic Speech in Madison Square

Garden, New York

- A must see!

- A must see!

"War on Terror" -

on Israel's behalf!

World Jewish Congress: Billionaires, Oligarchs, Global Influencers for Israel

Interview with anti-Zionist veteran Ahmed Rami of Radio Islam

- On ISIS, "Neo-Nazis", Syria, Judaism, Islam, Russia...

Britain under Jewish

occupation!

Jewish World Power

West Europe

East Europe

Americas

Asia

Middle East

Africa

U.N.

E.U.

The Internet and

Israeli-Jewish infiltration/manipulations

Books

- Important collection of titles

The Judaization of

China

Israel: Jewish Supremacy in Action

- By David Duke

The Power of Jews in France

Jew Goldstone appointed by UN to investigate War Crimes in Gaza

The best book on Jewish Power

The Israel Lobby

- From the book

Jews and Crime - The archive

Sayanim - Israel's and Mossad's Jewish helpers abroad

Listen to Louis Farrakhan's Speech

- A must hear!

The Israeli Nuclear Threat

The "Six

Million" Myth

"Jewish History"

- a bookreview

Putin and the

Jews of Russia

Israel's attack on US warship USS Liberty

- Massacre in the Mediterranean

Jewish "Religion" - What is

it?

Medias

in the hands of racists

Strauss-Kahn - IMF chief and member of Israel lobby group

Stop Jewish Apartheid!

The Jews behind Islamophobia

Israel controls U.S. Presidents

Biden, Trump, Obama, Bush, Clinton...

The Victories of Revisionism

By Professor Robert Faurisson

The Jewish hand behind Internet

The Jews behind Google, Facebook, Wikipedia,

Yahoo!, MySpace, eBay...

"Jews, who want to be decent human beings, have to renounce being Jewish"

Jewish War Against Iran

Jewish Manipulation of World Leaders

Al Jazeera English under

Jewish infiltration

Garaudy's "The Founding

Myths

of Israeli Politics"

Jewish hate against Christians

By Prof. Israel Shahak

Introduction to Revisionist

Thought

- By Ernst Zündel

Karl Marx: The Jewish Question

Reel Bad Arabs

- Revealing the racist Jewish Hollywood propaganda

"Anti-Semitism" - What is it?

Videos

- Important collection

- Important collection

The Jews Banished 47 Times in 1000 Years - Why?

Zionist

strategies

- Plotting invasions, formenting civil wars, interreligious strife,

stoking racial hatreds and race war

The International Jew

By Henry Ford

Pravda interviews Ahmed Rami

Shahak's

"Jewish History,

Jewish Religion"

The Jewish plan to destroy the Arab countries

- From the World Zionist Organization

Judaism and Zionism inseparable

Revealing photos of the Jews

Horrors of ISIS Created by Zionist Supremacy

- By David Duke

Racist Jewish Fundamentalism

The Freedom Fighters:

Hezbollah

- Lebanon

Hezbollah

- Lebanon

Nation of Islam

- U.S.A.

Nation of Islam

- U.S.A.

Jewish Influence in America

- Government, Media, Finance...

"Jews" from

Khazaria stealing the land of Palestine

The U.S. cost of supporting Israel

Turkey, Ataturk and

the Jews

The truth about the Talmud

Israel and the Ongoing Holocaust in Congo

Jews DO control the media -

a Jew brags!

- Revealing Jewish article

Abbas - The Traitor

Protocols of Zion

- The whole book!

Encyclopedia of the

Palestine Problem

The

"Holocaust" - 120 Questions and Answers

Quotes

- On Jewish Power / Zionism

Caricatures / Cartoons

Activism!

- Join the Fight!